By Curtiss Takada Rooks, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor, Department of Asian and Asian American Studies

My mother was Japanese. My father was Black (African American). My father was Black. My mother was Japanese. I am Black. I am Japanese. I am both. I am Japanese. I am Black. I am both.

Born during the post-WWII occupation and establishment of an ongoing U.S. military presence of Japan, my existence, and hence my “mixedness,” exists in the conflicting nexus of human interaction and government policy as both the U.S. and Japan eschewed interracial relationships, particularly among non-commissioned officers and enlisted men. But, human nature prevailed over policy, resulting in more than 50,000 marriages between U.S. military men and Japanese women between 1947 and 1965. And, so I was born into a bilingual, bi-national interracial Black and Japanese family.

U.S. military policy stationed servicemen returning to the U.S. with military (war) brides and interracial families in clusters at six military locations, including Fort Riley, Kansas, where my family landed. As a result, I grew up in a military environment with other families that looked like mine — Japanese and Black — along with other variations of interracial and international mixing. As children, we saw parents who were the same color and parents who were not. We spoke and heard languages other than English. We ate foods from all over the world, and in our kitchens created fusion culinary delights. In this way, throughout my childhood and youth I never imagined myself as a unicorn or, as one of my students once put it, “a walking issue.” In many respects, in this military family cocoon we viewed ourselves and our families as just another type of normal.

Don’t get me wrong, we also faced more than our share of taunts along with other forms of discrimination and alienation, much of it mean and nasty, but I never felt alone. Even if we, the children of interracial families rarely actively talked about it — our mixedness — we knew others shared “it,” that others “got it.” While stationed with my family on Okinawa in the late 1960s, my junior high friends and I were engaging in fledgling, adolescent political discussions when the conversation turned to communities of color self-naming and re-appropriating language, like Afro-American. During our musing I commented that, being mixed, I wondered what name fit me, “What was I?” Without missing a beat, a Japanese American friend from Hawaii said, “I know what you are, you’re Hapa-Afro.” He told me that “Hapa” referred to mixed race Japanese in Hawaii. In that moment it all made sense, questions about my identity as a mixed/multiracial person coalesced. It fit. I had a name and with that, I began to understand another important truth: I learned not to own other people’s spite. Still, this lesson was often hard to hang on to and sometimes the noise would drown it out because outside our cocoon, life was a vastly different matter.

Viewed through the societal tropes of either tragic mulatto and hybrid vigor (i.e., best of both worlds) persons of mixed/multiracial heritage bounced between invisibility to hyper-recognition. As tragic mulatto figures we existed as the living cautionary tale against interracial coupling and marriage. Torn between two worlds, unaccepted by either. Destined to a pathological life of internalized turmoil. Even as social mores relaxed a bit and Loving v. Virginia (1967) rendered anti-miscegenation laws unconstitutional, parents, teachers, pastors and others expressed in a kinder, gentler refrain for constraint given to young interracial couples during this period pleaded, “What about the children?”

At the turn of the 21st century, the hybrid vigor social narrative took root. Deemed the “best of both worlds,” the mixed/multiracial subject projected the future, before the future arrived. We were the living evidence of a post-racial society. The imagined post-racial America recast us from tragic hybrid degeneration to hybrid vigor, a siren hope for racial harmony.

As with all tropes and master narratives, nuance and complexity robs people of their subjectivity, their humanity. Today’s college students, born into these actively competing narratives, find themselves trapped in the spite and hope of others.

Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, I spoke widely on “mixedness” to student affairs, academic and public audiences. As a result, I was asked to develop and teach–what was then among the first courses in the discipline of Asian American Studies—a class that was devoted entirely to the question of mixed/multiracial experience(s). It was exciting. Invigorating. Scary. Undergraduates and graduates registered for the course and together we examined not only questions of mixed/multiracial identity and histories, but also the wider “so what?” What would the study of mixed/multiracialness contribute to wider discussions of the roles and epistemology of critical race, ethnicity and culture in social, political and economic explanation? What would the study of mixed/multiracial persons contribute to our wider understanding of biology, physiology and medical practices?

Much has changed since that first course, including the emergence of a robust multi-disciplinary literature on mixedness ranging from critical racial, ethnic and gender identity to bone marrow matches for blood-borne diseases and medication dosages. But, in the nearly 25 years since teaching that first class on multiraciality, in every offering students of multiracial and multiethnic heritage have echoed a version this refrain, “I didn’t know that there were studies about ‘people like me.’” They comment on how empowered they feel knowing that they are not alone. That reading stories (academic, fiction, popular) about themselves, because they never had that chance before, unless it was their research project, let them know they are not crazy. That their experiences are real and shared. That, importantly they learn a vocabulary, a language to research, talk and reflect upon their life experiences not compartmentalized within the larger story of … (fill in the blank). For the mono-racial students in these classes they remark first that they never knew or thought about how master narratives and tropes constricted their understanding of others’ experiences. Both groups recognize the need to challenge critically what we know and how we learned it.

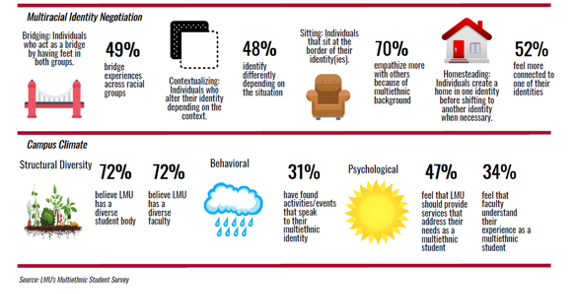

Several years ago, LMU embarked upon a journey to learn more about the lives, challenges and celebrations of students from mixed-heritage backgrounds. The Multiethnic Task Force comprised of faculty and staff, the majority of who were of mixed heritages, designed a multimethod research project that involved interviews, focus groups and surveys of students self-identifying as mixed. In broad strokes, the research found that while not totally invisible, the students felt the challenges of mixedness at LMU remain largely unrecognized and unmet.

This past academic year the LMU community, particularly within student development, focused on the notions of self care as an important component of the university’s commitment to whole person development. Understanding one’s self, being comfortable with the intersectionalities that comprise us, that make up our skin, is paramount in that self care. Research in student development calls on colleges and universities to pay closer attention to the growing complexity of racial and ethnic identification of our students, and in particular those of mixed-heritage backgrounds.

Earlier in this essay, I shared a portion of my mixed story and the importance of family and community in living mixedness as another form of normal. While I recognize that my story is not representative of all mixed persons, and may even be exceptional, I know that without the moment of naming – Hapa-Afro – my understanding of self would be very different.

My mother was Japanese. I am Japanese. My father was Black. I am Black. I am Japanese and Black. I am one. I am the other. I am both. (And, so much more …)

LMU’s Multiethnic Student Survey

Professor Rooks’ experience speaks to many of the challenges faced by multiethnic /multiracial students on our campus. In 2015, LMU’s Multiethnic Taskforce was created to address these concerns and develop ways that LMU can better serve students who are navigating their identities in this way. From 2016-18, the Multiethnic Student Survey was conducted.

Visit this interactive summary of the survey findings. From this project emerged five key recommendations on how better to serve multiethnic students at LMU.

Across all divisions and departments, our university works to cultivate an open, welcoming, and safe environment for faculty, students, and staff. As we learn more about the experiences of our campus community members, we can use our expanded perspectives and understanding to create programs and spaces for everyone to thrive.

OIA Buzz

- Quote of the Month: “The better we understand how identities and power work together from one context to another, the less likely our movements for change are to fracture.” — Kimberle Williams Crenshaw

- CONTINUITY OF COMMUNITY: Lion Connection

To alleviate some of the social distancing the current situation has created, the Office of Intercultural Affairs introduces Lion Connection, a fun and casual way to connect our community together! Through Lion Connection, LMU staff, faculty, and students will engage in a 30-minute virtual coffee with another community member, then later meet up with other pairs for a fun and friendly meet-up. Take this time to learn more about each other, share innovative ideas, and develop a connection in a fun way that can continue on after we have returned to campus.

If you are interested in participating in Lion Connection, please sign up here.

- CULTURAL CONSCIOUSNESS CONVERSATIONS: Increase your comfort level and build community with faculty, staff, and administration. Learn about the program and EXPRESS YOUR INTEREST in next year’s cohort.

- CONTINUITY OF COMMUNITY: Women’s Embodied Spiritualties: Join us for a different kind of DEI conversation — one that focuses on the women’s embodied spirituality. In this series of informal conversations, we will focus on the embodied, everyday character of our experiences, sharing and exploring across a diversity of identities, spiritual experiences, and religious backgrounds. Click here for more information and to sign up.

- Stay connected! Follow us on Twitter @LMU_OIA #StrengthenDiversity #OIASpotlight